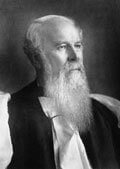

About the Author

John Charles Ryle (10 May 1816 - 10 June 1900) was the first Anglican bishop of Liverpool.

Even though J.C. Ryle was raised in a nominal Christian home, he once believed that Christianity must be one of the most disagreeable occupations on earth—or in heaven. But one day he happed  into a church where, hearing Scripture read out loud, he was transformed. One verse, and the emphasis made in between each clause, gripped him. “By grace are ye saved . . . through faith . . . and that not of yourselves . . . it is the gift of God.” Reflecting on his conversion, Ryle said, “Nothing to this day appeared to me so clear and distinct as my own sinfulness, Christ’s preciousness, the value of the Bible, the absolute necessity of coming out of the world, the need of being born again, and the enormous folly of the whole doctrine of baptismal regeneration.” And he never looked back.

into a church where, hearing Scripture read out loud, he was transformed. One verse, and the emphasis made in between each clause, gripped him. “By grace are ye saved . . . through faith . . . and that not of yourselves . . . it is the gift of God.” Reflecting on his conversion, Ryle said, “Nothing to this day appeared to me so clear and distinct as my own sinfulness, Christ’s preciousness, the value of the Bible, the absolute necessity of coming out of the world, the need of being born again, and the enormous folly of the whole doctrine of baptismal regeneration.” And he never looked back.

He was the eldest son of John Ryle, private banker, of Park House, Macclesfield, M.P. for Macclesfield 1833-7, and Susanna, daughter of Charles Hurt of Wirksworth, Derbyshire. He was born at Macclesfield on 10 May 1816.

Ryle grew up in a wealthy home, wanting for nothing, heir to the family fortune, in pursuit of a banking career, walking in his father’s footsteps. In 1841, however, his father’s investments collapsed and instantly his whole future changed. “We got up one summer’s morning with all the world before us as usual, and went to bed that night completely and entirely ruined.” He described that experience as “the blackest chapter of my life.” By fall of that year he applied himself to Christian service.

In December 1841 he was ordained by the Church of England and was made Rector of the Church of St. Thomas in Winchester; from there he moved to the parish of Helmingham in Hampshire, serving three years; and then he served thirty-six years in Suffolk. In 1880, after thirty-nine years of faithful ministry, he was made the first Bishop of Liverpool, in the Church of England. He was affectionately known as “the working man’s bishop.” And as a bishop he adopted one single text for his official work: “Thy word is truth” (John 17:17).

He was educated at Eton and the university of Oxford, where his career was unusually distinguished. He was Fell exhibitioner at Christ Church, from which foundation he matriculated on 15 May 1834. He was Craven scholar in 1836, graduated B. A. in 1838, having been placed in the first class in literæ hunaniores in the preceding year, and proceeded M.A. in 1871. He was created D.D. by diploma on 4 May 1880.

Ryle was trained at Eton College, then at Oxford. Commenting on his very deliberate writing technique, he said, “In style and composition, I frankly avow that I have studied as far as possible to be plain and pointed and to choose what an old divine calls ‘picked and packed words.’ I have tried to place myself in the position of one who is reading aloud to others.” He credits William Cobbett, the political radical; Thomas Guthrie, the Scot; John Bright, the Quaker orator; John Bunyan, Puritan and author of Pilgrim’s Progress; Matthew Henry, the great biblical commentator; and William Shakespeare, of course, as influences on his pen.

Ryle was a strong supporter of the evangelical school and a critic of Ritualism. He was a writer, pastor and an evangelical preacher. Among his longer works are Christian Leaders of the Eighteenth Century (1869), Expository Thoughts on the Gospels (7 vols, 1856-69), Principles for Churchmen (1884). Ryle was described as having a commanding presence and vigorous in advocating his principles albeit with a warm disposition. He was also credited with having success in evangelizing the blue collar community.

J.C. Ryle was a theological vertebrate. He never suffered from what he called a “boneless, nerveless, jellyfish condition of soul.” His convictions were not negotiable. Indeed, his successor described him as “that man of granite.” Archbishop Magee called him “the frank and manly Mr. Ryle.” Charles Spurgeon said he was “an evangelical champion . . . One of the bravest and best of men.” Ryle simply observed, “What is won dearly is priced highly and clung to firmly.” And his fortitude was not limited to doctrinal matters. As a best-selling author he used his royalties to pay his father’s debts. True character is not for sale, neither does it owe any man.

J.C. Ryle died on Trinity Sunday, 1900. At his funeral, “The graveyard was crowded with poor people who had come in carts and vans and buses to pay the last honours to the old man—who had certainly won their love.” Canon Hobson, speaking in Ryle’s memorial sermon, said, “Few men in the nineteenth century did so much for God, for truth and for righteousness among the English-speaking race, and in the world, as our late Bishop.” Bishop Chavasse, His successor, said he was a man “who lived so as to be missed.”

From his conversion to his burial, J.C. Ryle was entirely one-dimensional. He was a one-book man; he was steeped in Scripture; he bled Bible. As only Ryle could say, “It is still the first book which fits the child’s mind when he begins to learn religion, and the last to which the old man clings as he leaves the world.” This is why his works have lasted—and will last—they bear the stamp of eternity. They contrast fruit which “remains” (John 15:16) against wood, hay, and stubble. Today, more than a hundred years after his passing, these works stand at the crossroads between the historic faith and modern evangelicalism. Like signposts, they direct us to the “old paths.” And, like signposts, they are meant to be read.